Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

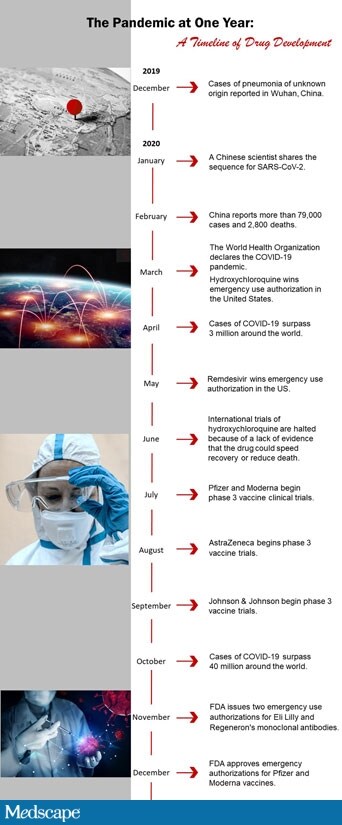

This time last year, hospitals in Wuhan, China, reported the first cases of pneumonia of unknown origin; it seemed unlikely at the time that a small number of patients coughing with shortness of breath would mark the beginning of a global pandemic that would kill more than 1.7 million people in a year.

Yet it is a scenario that John Brooks, MD, chief medical officer of the COVID-19 response at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), had trained for in advance.

But, he says, all the drills on pandemic flu hadn’t prepared him or the healthcare system for the way COVID-19 would spread, present, or need to be diagnosed.

“No!” he exclaimed.

Brooks recounts grim cases of patients filling up with clots, hearts going floppy from myocarditis, and lungs ― not just the membranes but also the blood vessels that carry nutrients for gas exchange ― getting clogged.

“People who had no symptoms of illness were falling over from stroke,” Brooks points out. And then came the strange rashes and a spectrum of illness “so broad and unexpected that it caught people by surprise.”

Detecting Cases

Nearly 79 million people have tested positive for COVID-19 so far. Diagnosing the illness and identifying SARS-CoV-2 are not as simple as testing people when they have symptoms or relying on a narrow presentation of respiratory symptoms. Diagnosis has come to involve an ever-broadening list of symptoms that is still being refined.

But the core diagnostic protocol is always the same, said Andrew Morris, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto: take a history, examine the patient, and use lab tests to guide diagnosis.

That approach works for managing patients with severe COVID-19, but SARS-CoV-2 has a built-in bomb: people are more likely to transmit the virus before they know they are infected.

This is different from SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome), SARS-CoV-2’s cousins, or even the flu, Brooks said.

He says he remembers thinking, “Holy mackerel,” when evidence of asymptomatic and presymptomatic spread emerged. “There are a whole lot of people with this infection who are transmitting it and don’t know it.”

For public health, this meant that early messages that people didn’t need to worry about being tested for SARS-CoV-2 unless someone around them was actively coughing or ill were wrong.

For CDC officials, it meant they had to convince a weary public — initially urged not to buy masks so that healthcare providers would have enough — to invest in masks and wear them consistently and correctly.

For clinicians, it meant that early testing of symptomatic people was missing a cadre of patients who either weren’t sick yet or might never get sick but could transmit the virus.

“That’s a much bigger problem, because our tools really aren’t very good” at diagnosing asymptomatic or presymptomatic patients, Morris said. “The history isn’t helpful because they don’t know where they got it, and they don’t have any symptoms, so physical exam doesn’t help.”

That meant clinicians had to rely on tests to make an accurate initial diagnosis and to know whether the virus was still capable of spreading.

Right Test, Right Time

Because the virus was new, no one knew exactly which tests would provide the best result or what it meant when tests were positive or negative. So researchers went back to what they knew, thinking that the reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test they used to diagnose flu might work here, too.

And then the long tail of SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding emerged. Because PCR tests were being used initially to determine how long someone could continue to transmit the virus, this was a problem.

Brooks remembered a call from a mother of three early in the pandemic.

“She was in the basement of her house, hadn’t seen her kids in 4 weeks, she keeps testing positive, keeps testing positive” by RT-PCR testing, he said. But she wasn’t contagious; she was just shedding pieces of virus that couldn’t replicate, so she couldn’t infect other people.

Over the year, clinicians have figured out a testing regimen. Early in the infection, the RT-PCR test is used to detect the virus with a high degree of sensitivity. Then, after a patient has recovered from symptoms, a follow-up culture is used to see whether viral genetic material picked up on PCR testing 10 days or more after recovery is replication-competent.

“Ten days after recovery, almost nobody is shedding virus that we can grow in a culture,” he said. This is now “the gold standard.”

Brooks said he thinks that antigen testing will continue to advance into 2021.

“What we’ve learned is that if you look at the bell curve of infection, where the amount of virus goes up and goes down as you go through infection, PCR can detect it for most of that curve,” he explained. “The antigen test really only gets you at the highest point, which is good; if you test positive, you are probably infectious.” Brooks said he hopes to find out next whether PCR testing can pinpoint the moment people are no longer contagious.

On December 4, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a dual flu/SARS-CoV-2 test for at-home use, which is more good news, Brooks said. He has ordered both that test and the SARS-CoV-2-only home test to see how effective they are. They haven’t arrived yet, so he can’t say for sure, but “they sure look cool; they really look like Star Trek.”

Morris said he agrees that easy-to-use self-tests will be important. “As we do more widespread testing that isn’t triggered by contacts or symptoms, I think we’ll get a much better portrait of the whole spectrum of illness,” he said.

The Vicious Cytokine Storm

The pandemic has reminded researchers such as David Fajgenbaum, MD, from the University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia, of the critical role of an effective immune response. It has also served as a chilling reminder of the destructive trail of immune dysregulation.

COVID-19 now joins the ranks of sepsis, primary and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and autoinflammatory disorders, such as Castleman disease, as possible causes of a cytokine storm.

Fajgenbaum has Castleman disease and knows first hand what it feels like when the immune system shifts perilously into overdrive.

“You start to lose consciousness and the brain doesn’t clear out the toxins. It’s incredibly painful when the liver and kidney start to shut down and fluid accumulates around the body,” Fajgenbaum explained. “All my organs were shutting down — the lungs, the bone marrow, the liver. It’s frightening.”

It is the same excruciating pain that some patients with severe COVID have asked for help with.

After his fifth relapse with Castleman’s, Fajgenbaum dedicated himself to finding a cure, but after the onset of the pandemic, his lab switched gears and began to focus on COVID-19. His team is now evaluating whether any of 350 existing drugs can be used to treat the disease.

Finding Effective Medicines

The discovery of medications that can lessen the effects of COVID-19 for some patients has led to a substantial decrease in death rates for hospitalized patients since the peak early in the pandemic. No therapy can eliminate the virus, but much has been learned this year.

A lot has already changed in the ICU, said Lewis Kaplan, MD, president of the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“When we started with this, we had a well-embraced philosophy that people were in need of rapid rescue with invasive mechanical ventilation,” he explained. “We then learned about specific phenotypes for patients who had lung injury, and we learned that many patients were manageable with noninvasive ventilation.”

Then the benefits of proning, whether or not patients are on ventilators, emerged. It’s something people not in intensive care can try on their own, Kaplan said. It can help empower them when they feel powerless.

Then came the trials to see which medications might help.

“Some of these were approached with deep conviction ahead of science,” Kaplan said. “One of them was hydroxychloroquine,” but data later revealed that it doesn’t benefit COVID-19 patients and, in fact, has potential harms.

The corticosteroid dexamethasone reduces mortality and works best for patients on mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen, said Daniel Kaul, MD, an infectious disease specialist from Michigan Medicine in Ann Arbor. “It probably has a much more modest benefit for people on low-flow oxygen and may have a harmful effect when given early to people who are not on supplemental oxygen,” he said. And “it absolutely should be avoided in the outpatient setting.”

The antiviral remdesivir (Veklury) was found to be of modest benefit when given to patients on low-flow oxygen. However, for people on high-flow oxygen, the benefit is unclear, and for those who are undergoing mechanical ventilation, there does not seem to be any benefit.

So far, no one has been able to show a mortality benefit with remdesivir, so the only advantage is a shorter hospital stay, Kaul said. “It makes sense that remdesivir works better when given earlier and that steroids work better when people have gotten sicker, at least 7 days from symptom onset,” he said.

Other ways to quiet the immune system, such as with interleukin-6 inhibitors, have not shown convincing improvements and should only be used in clinical trials. Such drugs include tocilizumab (Actemra) and sarilumab (Kevzara).

Two monoclonal antibody preparations — bamlanivimab and the combination of casirivimab and imdevimab — have received emergency use authorization from the FDA.

However, “they don’t seem to work once someone is hospitalized,” Kaul said.

There is still no proof that convalescent plasma — which uses antibodies from patients who have recovered from COVID-19 to treat persons currently infected with the disease — is effective, he pointed out.

“If it’s going to work, it’s likely going to be when it’s given relatively early,” he said.

The Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib (Olumiant) shows a modest benefit when given to patients on supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation; they get better a bit faster.

However, it’s much more expensive than dexamethasone, “and we don’t know if it adds any benefit to dexamethasone. Its role is quite unclear, even though there’s an emergency use authorization out for it,” Kaul explained.

A number of over-the-counter therapies — from vitamin C to zinc to famotidine (Pepcid) — are also under consideration.

“It’s entirely possible they are useful in specific populations,” Kaul said.

Treatments will continue to evolve even after vaccines are rolled out, so advances are shaping up to be as fast-paced in 2021.

There might actually be easier ways to administer drugs, such as with inhaled formulations of remdesivir or subcutaneous injections of some of the antibody preparations.

Dr Anthony Fauci AP

“There’s still a lot of work that needs to go on in terms of how to best treat people who get severe COVID-19,” Kaul said. “We also need to see how these treatments work in immunosuppressed individuals, children, and pregnant women, who are largely excluded from trials.”

Studies of children and pregnant women could begin as early as January, according to Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

In a July interview, Fauci told Medscape that he is grateful for health teams that care for patients. “I want to express how much I admire the real heroes on the front line for getting in there every day and essentially putting themselves at risk,” he said. “I’m operating from a different vantage point where I am, but I miss the days of being in the trenches with you.”

Fauci acknowledged that it’s been a stressful year, “but this is not something that is going to last forever. We’re going to get through it, and we’re going to look back and hopefully say we really gave it our best shot.”

Allison Shelley is executive editor for Medscape Medical News who reports on the COVID-19 pandemic. Heather Boerner is a medical reporter based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Her book, Positively Negative: Love, Sex, and Science’s Surprising Victory Over HIV, came out in 2014. Marcia Frellick has written for the Chicago Tribune, Science News, and was an editor at the Chicago Sun-Times. Ingrid Hein is a science journalist in Montreal, Canada, where she has been filing more stories about infectious diseases in 2020 than ever before.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.